Getting Intimate with…

Vaneet Mehta

August 30, 2023

Interviewed by Laura Clarke

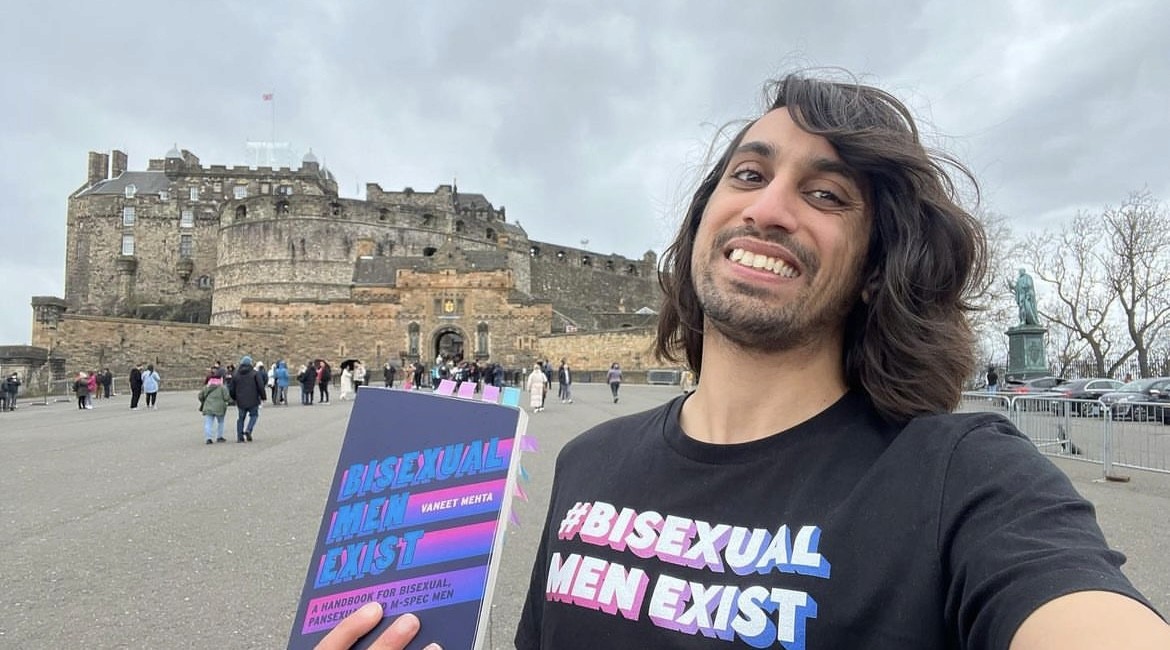

Vaneet Mehta (he/him) is a bisexual activist and writer who started the hashtag #BisexualMenExist in 2018. He is a prominent voice in bi spaces, and earlier this year he published his first book — Bisexual Men Exist — named after the movement he founded.

In this edition of Getting Intimate, Vaneet talks about the inclusion of closeted folks in bi research, the links between misogyny and biphobia, and the nuances of intersectional activism within a community that is still fighting for basic recognition.

When did you create the #BisexualMenExist hashtag, and where did the inspiration come from?

I first created it in 2018, and it was in response to some of the biphobia that I was seeing on Twitter, specifically targeting bisexual men. Often on Twitter, when stuff like this happened, I ended up getting involved by quote tweeting the biphobic tweets and getting wrapped up in it. But this time, I didn’t want to do that. I was sad and depressed by the whole thing, and I kind of just wanted to see something else.

And so I really just created the hashtag as an excuse for me and my mutuals share pictures of ourselves and celebrate and uplift one another. I also hoped that if anyone else was seeing the negative posts, they would see the positive stuff instead, and maybe make some new friends.

In 2018, I didn't have much of a platform, so it got a lot of engagement for me at the time — a few hundred likes and retweets. I met a whole bunch of people, and we all followed each other, so that was lovely.

Then, in 2019, I used the hashtag again for a very similar reason. It was after the Love is Blind episode aired, where Carlton came out as bisexual. I didn't personally watch the show, but there was often a lot of chatter online about what happened in the episode, and so much of it was biphobic. There was a poll going around asking, “would you date a bisexual man?” A lot of people were saying no, and there were so many disgusting, vile comments underneath it.

And so I reignited the hashtag. I thought, “I'm not going to engage with all of these people. I'm going to engage with my friends instead. And we're going to have a nice little moment.” I didn't think it would have the impact it did. Pink News, GLAAD and Stonewall all picked it up. Loads of bisexual men used the hashtag, including bisexual men who hadn't even come out before. Bisexual men who were saying “I'm not confident in my bisexuality, but here I am”. And that's what really galvanised me to write the book. It's something that I've written about a lot in the past, from the perspective of being a bisexual man and my experiences, but I really wanted to create a book that highlighted more than just me and really talk about the structures at play, the discrimination that happens on a much wider basis and how that impacts individuals from across the world.

One of the things that struck me about the book was how thoroughly researched it was. Do you have a favourite fact or concept that you learned throughout your research?

I spoke to a lot of different people for the book, so I learned a lot about experiences that were outside of my own, which was really interesting to me. People spoke to me about their experiences with sexual violence, the AIDS crisis and getting tested, experiences in the community — some of which I had — but not in the same way that others did.

It was important to me to have people's lived experiences to ground the book. But I also really wanted to back these experiences up with research about the structural issues at the same time.

I found out information from Galop about the rates of sexual violence amongst specifically bisexual and pansexual men. I researched the lack of HIV and STI testing and awareness in the bisexual community. There was a lot where I had already known that there was an impact, but I didn’t realise how deep it went.

There was an instance that really shocked me where a bisexual man was sued for his bisexuality by his ex-wife.

That was one of the parts that shocked me the most. I actually read it out loud to my partner like “can you believe this?!”

There’s another part where I speak about a paper where they measured men's penises when they were aroused by pornographic material to see if they were bisexual. To determine what their identity was.

And so there was a lot of stuff like that, which is outside of my lived experience, where I just read it and went, “what the hell?”

Despite the title of the book, Bisexual Men Exist, not everyone who participated in your research identified as a man or used the term bisexual. Why was it important to you to keep the research inclusive of those with more non-binary or fluid identities and people who use other terms to describe their sexual orientation?

I really wanted to drive home the point that these experiences aren't limited to only bisexual men. “Bisexual” is a word that is well known, so it needed to be on the book, and it's the term I identify with, which is why it’s the hashtag. But the experiences go so far beyond us.

There are people who were socialised as men or assigned male at birth and therefore have had similar experiences to us because of that. They may not have come out as non-binary, genderfluid, etc. until later on in life, meaning that the experiences they had in some ways align with our own.

For the same reason, I use “M-spec” throughout the book, which stands for Multi-Gender Attracted Spectrum. While not everyone uses the word “bisexual” and may use other terms, there’s a lot more that we have in common than sets us apart. What I don't want to say is, “well, you're basically the same as us” because that's not true. There are specific experiences that, for example, pansexual people will face. But I wanted to stress the point that there is an overarching issue that impacts everyone. It's such a wide community that is being impacted.

You speak in the book about phallocentricism and how bisexuality is seen as “just another flavour of gay” — how does biphobia such as this link into other forms of oppression like homophobia and misogyny?

I often say that the root of homophobia is misogyny. It's this idea that gay men are lesser, weaker and more feminine. And I think that there's an overlap between biphobia and homophobia in a similar way. Biphobia gets erased as if it doesn't exist — we are assumed to be gay, and then we get homophobia as a result of that. Going back to the Twitter poll, people were saying “no, I wouldn't have sex with a bisexual man because he's had a dick up in him, and that's disgusting”. That's just homophobia. But it’s also biphobia. It’s really difficult to separate one from the other.

The reason that a lot of bi men find it so difficult to come out is internalised biphobia. It's feeling that your identity doesn’t exist and that this isn't something you can be. But it's also internalised homophobia. A lot of bi men choose to identify as straight over gay, and it's because of the fear of homophobic abuse.

Phallocentrism has a really big impact in so many different ways that a lot of people don't seem to realise. For example, virgin culture, the whole purity culture, focuses on the idea that once a woman is penetrated, they're changed; they’re altered. So women who have had sex with lots of different men are seen as sluts.

It’s the same with homophobia and biphobia— the idea that you're robbed of your masculinity once you’ve had sex with a penis, that it's taken away from you. Bi men are seen to actually be gay men because they’ve been penetrated. Your sexuality is defined by the fact that you have had that sex with a penis.

We know that bisexual people are statistically more likely to experience difficulties with their mental health, not inherently because they’re bi but often due to the minority stress that comes with the identity. In your opinion, what is the best way to support m-spec men with mental health conditions in a way that doesn’t pathologise or victimise, especially when men may find it harder to talk about their feelings due to toxic masculinity?

I think the way that a lot of health professionals can support bi men is firstly by just believing us, because I think a lot of them have a very hard time in simply believing in our identity. And that causes a lot of problems.

I think the issue is that you find a lot of therapists who understand how to do the therapy part. But they don't necessarily understand the difficulties of different lived experiences. And so when you go to them and say that you’re experiencing depression and anxiety, and that is because of the fact that I am abused and shamed for my identity, they don't understand how that can play into the depression.

I remember talking to a therapist and telling her that I was finding it quite difficult because I didn’t feel accepted in the community, being bi and being Asian. And it just went right over her head. She was like, “oh, so why do you think that?” She made me feel like it was all in my head.

I think it's so important to learn about the lived experiences of your clients. You need to know about the lived experiences of black people, brown people, bi and queer people. You need to know this stuff because otherwise you can't support us. If you don't understand biphobia, how can you support bisexual people?

In the book, you talk about the difference between MSMW (men who have sex with men and women) and those who actively identify as M-spec. In research, what is the importance of recognising behaviour versus identity?

It's important because the lived experience can be very different. There is going to be a difference between those who are having sex with people of different genders and are still identifying as straight versus those who are out as M-spec.

For people who are in the closet, and maybe their behaviour differs from their identity, there may be internalised issues that they can't deal with. Maybe they just want to identify as straight, which is valid. But it's about unpacking that and seeing if there are internalised issues? These people may not be accepting their identity because there's an internal problem, and that's due to the external problem of monosexism and the general erasure in society.

Not being out sometimes also leads to more risky behaviours. People who are in the closet may not have access to certain resources and services because they're not in the community. They may not have knowledge about safer sex. They may not be going over to people's houses or going to a queer venue, but instead having sex in a back alley where no one will see them.

If you're only looking at one side of the picture — people who openly identify as bi — you’re going to lose half the information.

One of the most interesting concepts in your book was the idea that queerness has historically been less accepted by white, western counties, but that now we claim progress as ours and condemn non-Western counties and cultures for their “backwardness”. How do we continue to progress while a) taking accountability and b) not rewriting history?

I think it's really about uplifting queer people of colour and our voices. I think that's the only way to do it.

And maybe taking accountability takes the form of checking privilege and really making sure not to overstep in a conversation. I think often when there’s a discussion surrounding the treatment of queerness in another country, “this is so awful” spills quite easily into racism.

It really does. We're so prone to using other countries as scapegoats. I’ve heard so many people claim that homophobia and transphobia don’t exist in the UK because “in another country, you’d be killed.”

People also love to say stuff like “I'm illegal in *this many* countries”. But actually, it’s likely that no-one would care because you're just seen as a white person who's doing a white person thing. Ultimately, I think the way to make progress is to not only support queer people of colour in this country but also find ways to support them in other countries.

I think the work that the Kaleidoscope Trust is doing is great in terms of going over to other countries and helping activists who are doing the work there. Supporting them rather than overriding them and taking over the conversation.

Your book is incredibly intersectional, and you explore bisexuality and race in a way that I’ve not seen elsewhere, especially regarding bi men. Do you think that the conversation about bi men of colour is being neglected? And what are the key issues there that you think we should be discussing?

I think the reason why it's probably being neglected is because the bisexual community is still just fighting for even a modicum of visibility. Therefore, it's so difficult to even have any kind of intersectional or more nuanced conversations because we're still doing Bisexuality 101.

I remember when I made the hashtag and people were like, “I don't want to have to keep saying we exist”. And I understand that. It’s just the beginning of the conversation, but sadly, people still don't believe it.

I think the other part of the problem is that the bi community, like the LGBTQIA+ community as a whole, is very white. And therefore, it's so difficult to exist in that space as a bi person of colour. Our conversation gets missed.

But I do believe that the community supports me. I feel like the bi community supports me in a way that the general LGBTQIA+ community often doesn't.

What was a question that you used to have about bisexuality, and could you answer it now for anyone wondering the same thing?

Well, in my teen years, I didn't even know it was a word, but I was like, “how can I like this and this?” That was my question. Can I even be this thing?

For so long, I was internalising that it wasn't a thing I could be, that it didn't exist. And I think that's why I often come back to the bisexual men exist phrase, because I think some people do need to hear it. People like me, — ten years ago, I needed to hear that.

So, I honestly would say the title of my book, which sounds really narcissistic of me, I guess? (Laughs)

(Laughs) Not at all. There's such power in these hashtags and these movements.

I just wish someone had said to me, “hey, this is an identity you can be. You don't have to make a choice between gay or straight”.

I think if someone just told me that, I would have been like, “okay. Let's do it.”

Getting Intimate is the blog series where we interview people making a difference in the world of sex, relationships, gender and feminism. Read more interviews here.

If you want to learn more about Vaneet and his work, check him out on his socials:

Twitter: @nintendomad888

Instagram: @nintendomad888

For more sex and relationships content, follow My Body & Yours on Instagram (@mybodyandyours)

Interview Date:

July 5, 2023